In linguistics, lexis – Lexik in German – is the entirety of all possible words in a language in its spoken and written form. While we can use writing to depict the entire lexis, the script itself is not a language. It has a structural relationship to the spoken language. Using consonants and vowels, it is a visual translation of the acoustic. First and foremost, it is the visual realisation of language. Despite their distinct form, individual letters are not signifiers able to convey complex content. Yet they do communicate a visible mood as the (type)face, the depiction of text: Speech becomes a visual, aesthetic experience. Like language itself, this depiction can take on a range of different forms. Character shapes and scripts change over the course of time. Fonts are variable. They each reflect the technological developments and fashion trends of their period. In the same way, opinions and perceptions of contemporary representation evolve. All of that provides ample reason to re-asses letterforms again and again. There are countless versions and variations of script, whose classifications can be read to reveal the multifarious history of writing. More than anything, however, they are the result of steady purpose-bound assessments of how to best design letters. «Perhaps less widely appreciated, but just as significant, the printing of information has served not only to record and pass on information as expressly intended, but it has also provided another set of messages, or history, through the visual, formal qualities laid down in the type. These visual, formal qualities are also the unwitting testaments that can provide an insight into the intellectual, spiritual, manual and technological climate of an era.»

Roger D. Hersch further notes in his ‹Visual and Technical Aspects of Type› (Cambridge University Press, 1993) that there is an enormous gap between modern-day technology and the inherited standards of typographic art. ‘Typographic creativity’, as facilitated by new attainments, has only lead to a mere adaptation of established printing types without making a real contribution to a further development of the understanding of their cultural and psychological effects. We can make up for such defects by returning our gaze to the cultural and historical aspects of letterforms, retracing the historical correlation between the shapes of letters and the intellectual and spiritual level of the culture that brought them forth. Roger D. Hersch writes that technological progress does not have to exclude the historical perspective: «indeed, [technological advances] can incorporate the advances in visual and formal qualities that are the result of a long evolution. As once before, letterform and the technology used to reproduce it can proceed in partnership in the advancement of civilization as they have done for over two millennia.»

In his essay ‹Typeface as Program› in the publication of the same name (by François Rappo), Jürg Lehni addresses contemporary computer and software technologies, describing them as a simulation of originally analogue or mechanical processes. The computer takes on the role of a machine that simulates other machines or processes, essentially acting as a meta-tool. Software is largely defined thus, so that computers generally serve as substitutes for already existing process-es. The same is true of the forms used in the development of the Lexik typeface. It is not the direct digital translation of a model, but rather, so to speak, a simulation of historical inscriptions. The elementary re-search set out primarily from Renaissance Antiqua typefaces, simulating their putative tools. Yet there was neither an actual tool to be used, nor a concrete drawing to act as a model. We did have: perceptions and insights on the workings of widening and narrowing (thick and thin) in broad nib styles, and a collection of inspirations taken from the shapes of historical finds. That is the ground from which we transformed the digital tool into our own design tool. We followed the rules we had established. We are aware that strict, regular forms within a constructed and consistently applied type create a coherent and stringent style that may have a good visual effect but will be much quicker to fatigue the eye of the reader. An irregular, organic appearance, on the other hand, is more ergonomic for the human eye. So we set out to break our rules whenever possible, and worked on each letterform individually. Thus removed from a calligraphic tradition, this process enabled us to use the digital tool to our ends: introducing agility into the typeface and setting ourselves apart from the Antiqua types that are rooted in calligraphy.

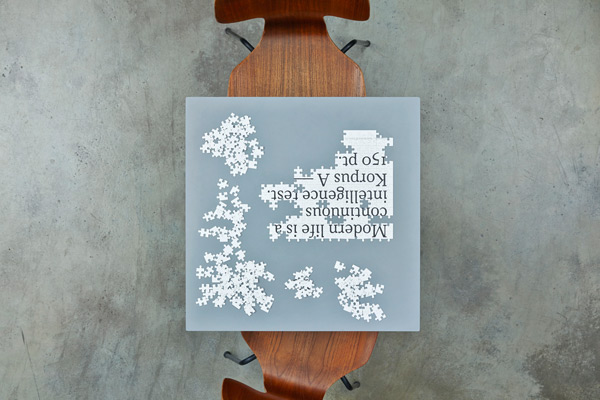

The tool of our work is the computer. Authors Martina Fineder, Eva Kraus and Andreas Pawlik addressed the phenomena of the computer era, which call for a discerning eye, in their preface to the publication ‹Postscript›. This transitory collection includes examples that span the range from loving historical preservation and reappraisal of traditions to programmatic eclecticism and formalist caprice. Analyses touching on the development of the Latin alphabet focus on the search for new interpretations. The featured notion of a type design process of ‹copy what you want and use it as you wish› inspired our approach to the ‹Lexik› typeface, borne out of the desire to investigate a principle of this kind in serious research and create an Antiqua typeface that does justice to contemporary needs. It is part of the design approach to cite familiar forms and the stories connected to them, bringing with them the original material they bear within. Our aim is not to directly reap-praise historical material or available templates, but to seek out new systems that reveal all qualities of type across media and sizes. It is not a novel demand that a typeface be suitable for body text and at the same time have display qualities. Where types used to be drawn and cut with visual adjustment for the given different sizes, Lexik accommodates the entire range of different applications without such adjustments. We always focused on the combination of the impression of individual characters on the one hand and function on the other. We may describe this in terms of a different interpretation of the particularities of micro and macro typography: micro for the formal depiction of character units, macro for the greyscale of the text, the ergonomic legibility arising out of its typographical depiction. A person reading a good text in order to delve into its contents does not invite disruption – by noise or disquiet, or indeed by the typeface and the characteristics of its appearance. We therefore had to consider culturally established reading conventions as much as the technological requirements of reproduction on screen and in print as reference points for all our decisions in the process of developing the ‹Lexik› typeface.

Lexik plays with reference and interaction between citation and sampling. Sampling implies seriality. Let us consider our script to understand the serial aspect of type design. With all its processes and back-references as well as the resulting output, a series appears as a chain, thereby removing itself from the single process and individual work. Understanding our alphabet as a system of symbols and from the point of view of its function – producing text –, we see that the individual letters of a type are episodes within a composite rather than (or at least in addition to) representing separate individual works. Within the compound of a text, they are but a fleeting moment within a greater occurrence, shrinking into relative insignificance. As an individual character on its own, however, each letter of the alphabet relates to all the letters that have preceded it and becomes itself a point of reference for all those that follow. That means that the individual character is ex-posed to perpetual back-referencing within its own system and moreover bears a historical connection to all characters. Even the entirety of our alphabet or set of characters (type) finds itself within a chronological connection to the past and the present.

The lexis of a language can equally be considered a series. The words and their meanings, inscribed by conventions, are subject to permanent cultural, temporal and contextual change. Language is variation not only in its appearance, but also its content. The concept of the series therefore represents the constant change in a thing. A series can even abandon its heroes: the old-fashioned hero dies, but the series goes on. The same is true of terminology and types that have be-come old-fashioned: Setting a book in blackletter type (Gothic script) has become an unlikely choice these days. Episodes (series) also imply the development of a thing. They encompass not merely repetition for the purposes of a copy, but copying for the purposes of continuation. The original – as in the origin – thereby becomes less important, it is undermined and disempowered. By way of this continuation, each depiction within its time contains its own original that manifests itself topically and in the moment. The thing itself, in our case the ‹Lexik› typeface, is therefore inherently not ‹old-fashioned›. This line of think-ing makes apparent why it is that perpetual re-interpretation is such an important part of the present. That goes beyond the type design: the series, i.e. the contemporary, is ever-present.

Let us return to the term lexis – ‹Lexik› –, looking at its relationship to the name of the typeface from a different point of view, the coincidence of its references. The Renaissance as a time of transition into the modern period is concrete and material; many things first came to wid-er attention, many things were first named and many old words were given a new meaning. The Roman Antiqua typeface developed out of the perspective of the humanist worldview, emerging in the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance. It was a recourse to Antiquity – the ancient Roman world –, and a paradigm shift that would lead the way to the future as printing came to the fore. It was a time when many linguistic elements transferred from oral sources, from the people, the world of the spoken word into the system of written language as new words. The lexis of almost all branches of science and academia arose mostly out of speech and entered the context of written language. Yet, as Mikhail Bakhtin described, the Renaissance was the very time when the sciences fought a battle for the right to think and write in the vernacular, the language of the people. This created a greater awareness for the notation of speech, intonation and syntax of written language and thereby expanded the vocabulary. It was the right time for a new, extended lexis. This insight combined with our research on Renaissance Antiqua typefaces to create coinciding references that inspired us to name our typeface ‹Lexik›.

Essay by Michael Mischler, Nik Thoenen, 2024