Grey — Blur — Aura

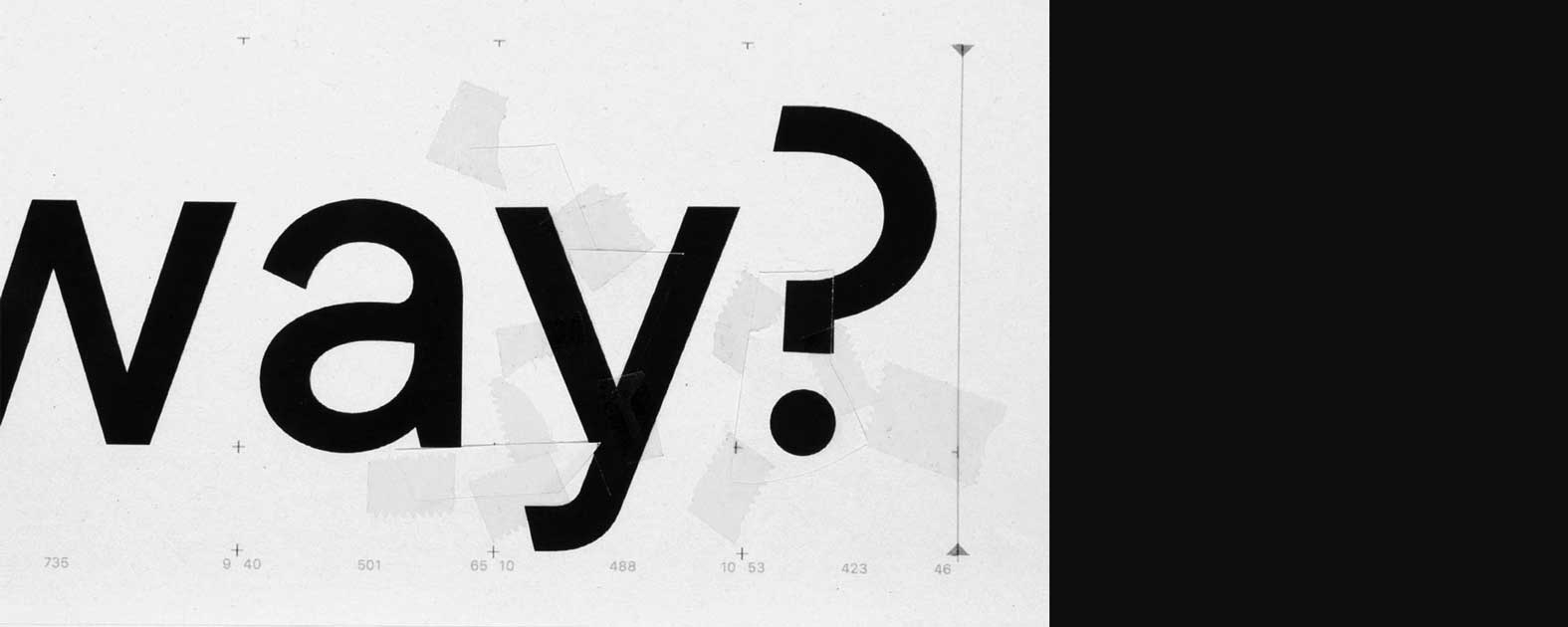

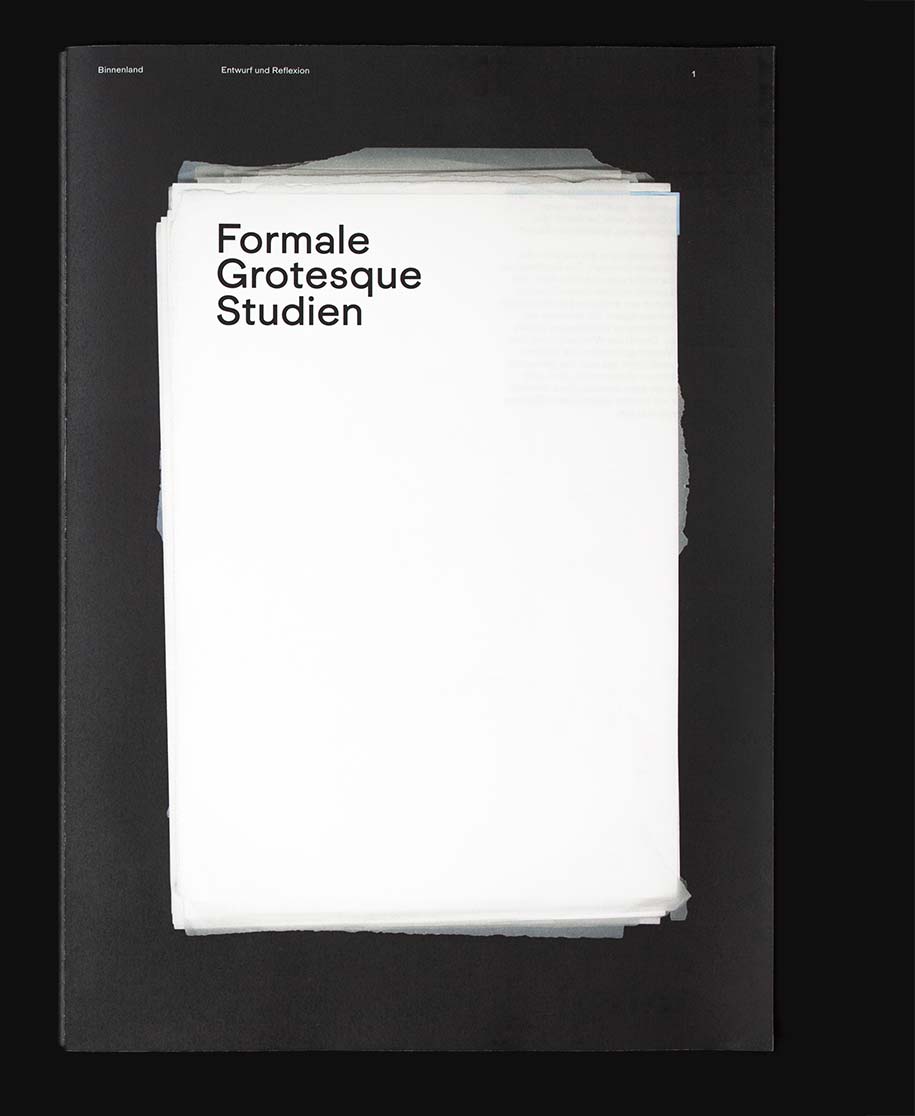

As we were developing the Formale Grotesque typeface, we began to wonder how we might be able to expand our creative repertoire and our design vocabulary. We thought about the aura of blur and those aspects of arriving at a design by analogue means of draughtsmanship entailed therein. We met type designer Stefan Willerstorfer to exchange our thoughts. His contribution about analogue sketching in the typeface design process to «Yearbook of Type # 4» (Slanted, 2019) describes the significance of the greyscale value. He writes about what is decisive to him in the process of sketching, of drawing in analogue form.

There is much talk about the significance of draughtsmanship, about sketching in the process of discovering a shape for a letter. Stefan Willerstorfer explicitly describes it in this particular phase as a greyscale value: the process of finding a more open definition of the distinctive boundary between black and white via the grey of a drawing and thereby finding a way of communicating the intention coherently yet still leaving open the potential of multiple interpretations. The decisions that must be taken can still be situated in the space that is made available by grey. We are not quite so discriminatory at this point: our focus is on the process rather than its goal. In this context, grey can also be described as blur, or aura. In the process of sketching, grey is a mediator for where the boundary will eventually be, where it will run between black and white, but without yet having to pin it down.

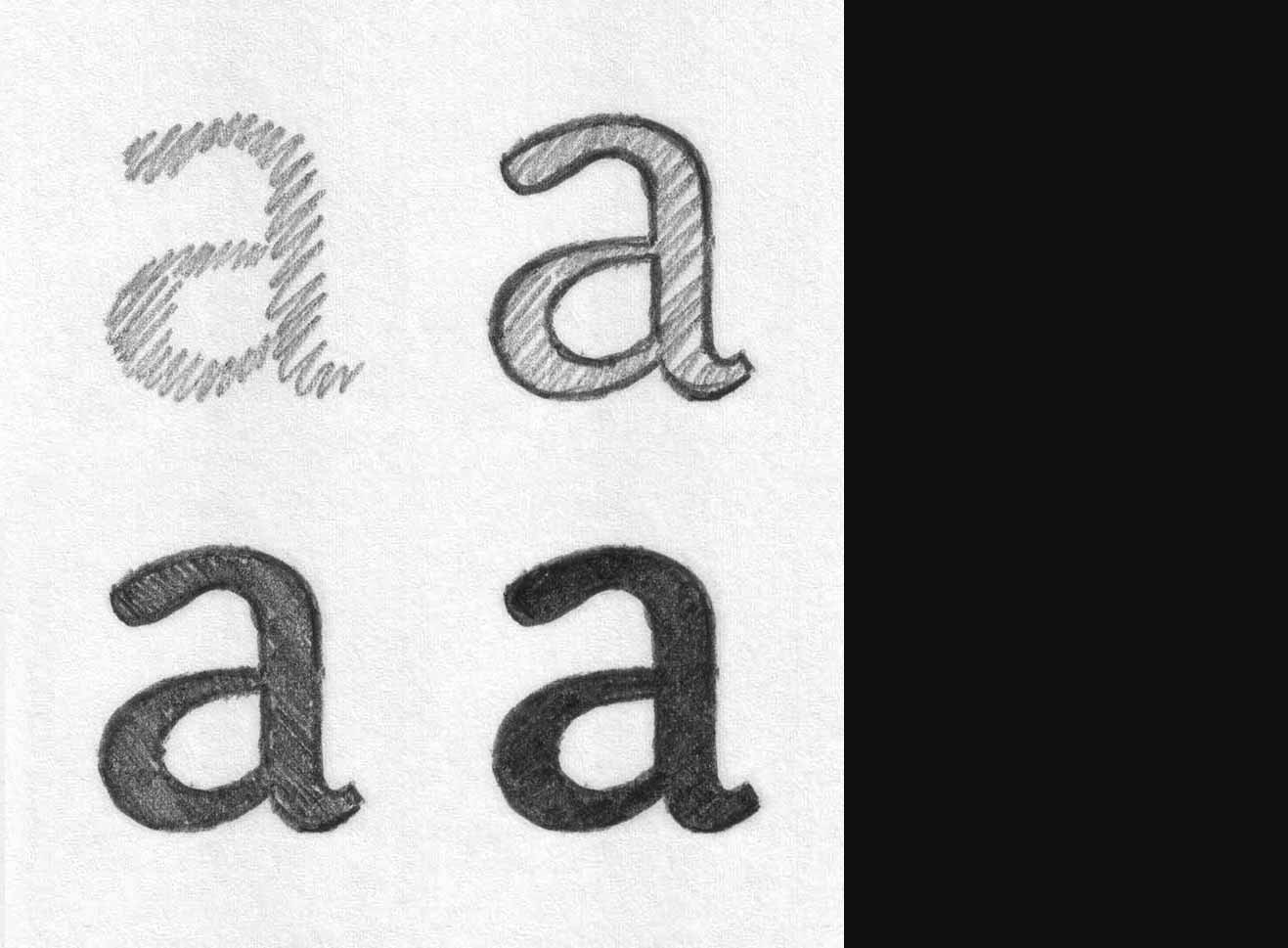

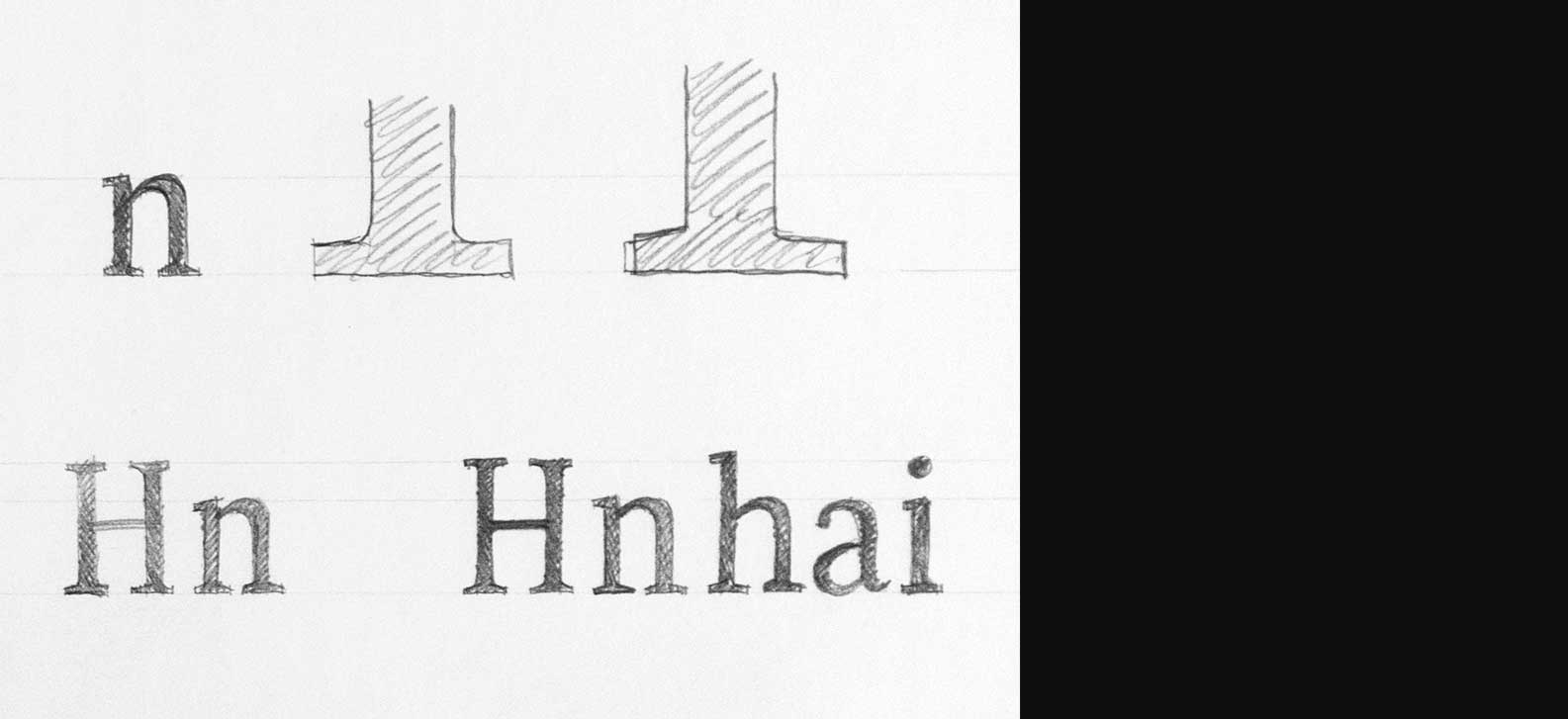

Stefan: When I start, I don’t go to the computer straight away – instead, I start with a sketch on paper. That strikes me as even more important when I work with letters than for other designs. I stick to the medium. Writing started on paper, and that is what I am designing the typeface for. Of course it could be argued that I am also designing for a digital medium, and hence I could only work digitally. But I feel closer to the hand-drawn sketch. For the upright glyphs, I start with a hatching technique in order to define the space of the character – approximately how much room it can take up. The outline will not be added until later. For italic glyphs, on the other hand, I like starting with the pen, the broad nib pen or the pointed pen, depending on which tool the typeface is supposed to be inspired by. In other words, I start by writing, and then I use transparent paper to go over it, interpret and give more focus to the designs. This is how I gain some distance to writing again and return to design to locate the form I want along this path.

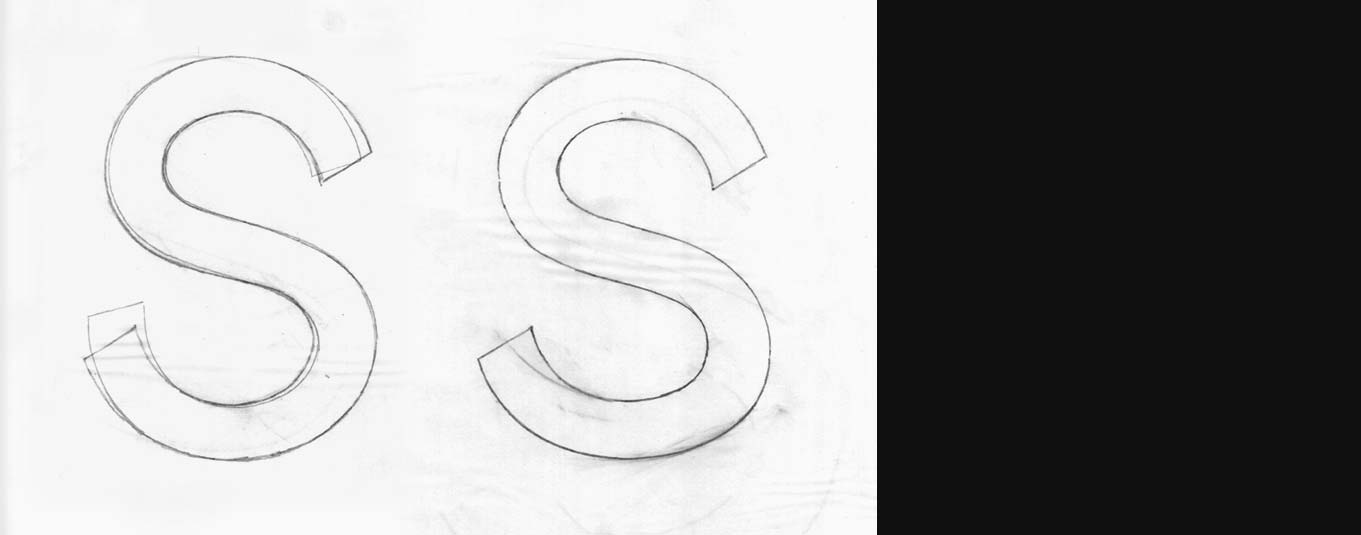

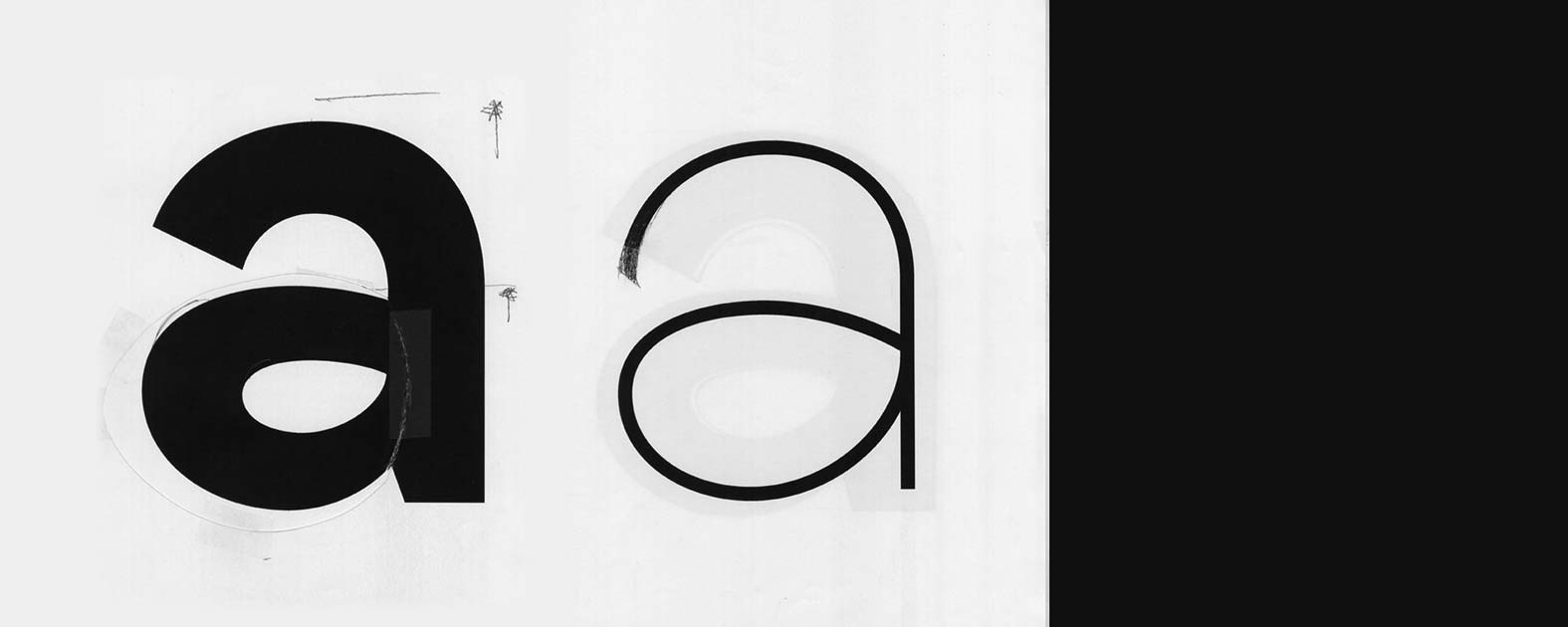

Hatching is still devoid of a defined boundary. The glyph still takes an auratic form, yet it is already imbued with proportions and reach within the associated ideas. The hatched form provides the basic structure, and it is within that articulation that the glyph will settle. We take a look at that process for the typeface Sindelar (Stefan Willerstorfer, 2014) at hand of four ‹a›s next to each other: the hatched one simulating the broad nib pen, the one equipped with an outline, and two others with additional hatching on top to gradually darken the gray value. This series illustrates his chosen method of working. The other sketches that are provided originate from the design process and yet they demonstrate how astonishingly close the sketch already comes to the finished Sindelar.